|

|

| Encephalitis > Volume 2(2); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

Although cognitive impairment is a known complication of acute encephalitis syndrome (AES), few studies have evaluated cognitive outcomes in patients with encephalitis. The primary objective of this study was to assess the cognitive profiles of patients diagnosed with AES, which is pivotal for improving rehabilitation strategies and prognostic measures.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital. Adult patients with AES who met inclusion criteria were enrolled. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tool was used to assess cognitive function at admission, discharge, and 3-month follow-up.

Results

Thirty-six patients were enrolled in our study. The mean age of the participants was 43 ± 18 years. Fourteen patients (38.9%) were female, and 22 (61.1%) were male. Tuberculous (TB) meningoencephalitis was present in 14 cases (38.9%), with herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis in 14 (38.9%), bacterial meningoencephalitis in 4 (11.1%), autoimmune encephalitis in 2 (5.6%), and Japanese encephalitis in 2 (5.6%). Patients with bacterial meningoencephalitis had the highest MoCA scores at admission, whereas those with HSV encephalitis had the highest scores at discharge and follow-up. Compared with the scores at admission, the scores at discharge and follow-up increased significantly in patients with TB meningoencephalitis and HSV encephalitis. The MoCA score at discharge was established as a significant predictor of cognitive function at follow-up.

Acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) is clinically defined as acute onset of fever and change in mental status with or without new-onset seizures. The term AES was coined in 2008 by the World Health Organization to streamline the surveillance and research of AES in India. AES results from an inflammation of the brain parenchyma and can be caused by a broad range of etiologies, including infections, autoimmune conditions, and chemicals/toxins [1].

Most cases of AES are secondary to a viral infection, with herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis being the leading cause internationally [2]. Though not common globally, Japanese encephalitis (JE) is the leading cause of AES in Asia [3]. Additional infectious etiologies include bacterial meningoencephalitis, tuberculous (TB) meningoencephalitis, enterovirus, adenovirus, scrub typhus, fungus, leptospirosis, neurobrucellosis, and toxoplasmosis [1,2,4]. The causative agents of AES vary with season, geographical location, immune status, and vaccination.

A wide range of differential diagnoses in the face of rapid neurologic decline requires physicians to act quickly in AES cases. Shortening the time between diagnosis and treatment is crucial because delayed management can result in neurological sequelae, including long-term cognitive impairment, personality changes, hearing or vision defects, speech impairment, convulsions, motor-sensory deficits, and movement disorders [5-7]. Although cognitive impairment is a known complication of AES, few studies have evaluated cognitive outcomes in patients with encephalitis [8]. Our primary objective in this study was to assess the cognitive profiles of patients diagnosed with AES, with the goal of improving rehabilitation strategies and prognostic measures.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee at Tribhuvan University Institute of Medicine (458(6–11-E) 2/074/075) and conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients, if possible, or their legal surrogates before enrollment. All subjects diagnosed with AES who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were admitted to the neurology ward of Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), Kathmandu, from June 20, 2018 to March 20, 2019 were enrolled. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

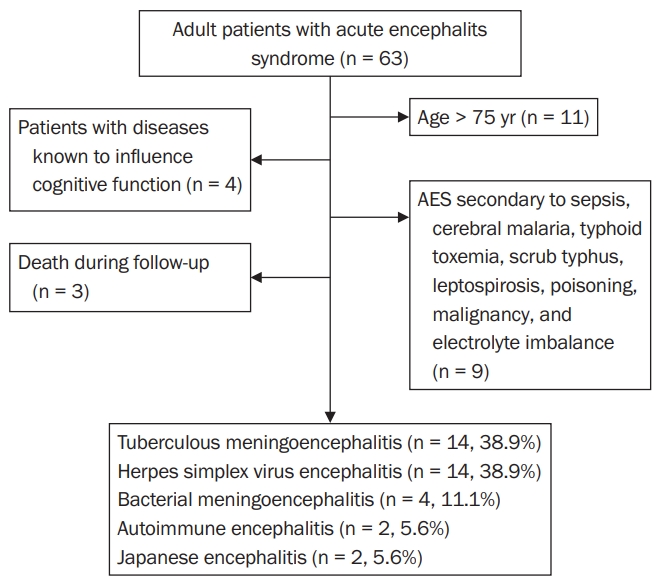

Adult patients with stable neurological and general health status with a clinical diagnosis of AES with or without comorbidities were included. AES was defined as acute onset fever with a change in mental status with or without new-onset seizures [1]. The following patients were excluded from our study: age less than 16 years or more than 75 years; patients with a neurological or psychiatric illness known to influence cognitive function; AES secondary to sepsis, cerebral malaria, typhoid toxemia, scrub typhus, leptospirosis, poisoning, malignancy, or electrolyte imbalance; and death during follow-up.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the cognitive profiles of patients diagnosed with AES. Cognitive function in each patient was tracked using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at admission, discharge, and 3-month follow-up [9]. If MoCA at admission could not be assessed due to core symptoms of AES (decreased level of consciousness, seizures, etc.), MoCA was administered after the patient’s general neurological status was improved and the patient was alert. MoCA is a rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. It assesses attention and concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuoconstructional skills, conceptual thinking, calculation, and orientation. The time needed to administer the MoCA is approximately 10 minutes. The total possible score is 30 points; a score of 26 or above is considered normal [9].

All patients admitted to TUTH’s neurology department with a history of fever and altered sensorium or seizure were evaluated for this study. Final enrollment was done according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The initial investigations were complete blood count, random blood sugar, electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, renal function test, liver function test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, hematocrit, and computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Lumbar puncture was performed in all patients, and the opening pressure was measured using a manometer. A routine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) investigation (total cell count, white blood cell differential, glucose, adenosine deaminase [ADA], and protein) was completed at the hospital-affiliated laboratory. Additional samples were preserved for specific work-up, such as CSF gram stain, culture, molecular testing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), protein or antigen testing, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) testing, antibody or autoimmune panel tests, and electroencephalograms (EEGs), as deemed necessary. Patients were treated and admitted to the neurology ward or intensive care unit, depending on disease severity.

Five etiologies for AES were identified in our study; mycobacterium TB, HSV, bacterial infection, JE, and autoimmunity. Diagnoses were based on clinical features, CSF analyses, imaging results, and laboratory tests. The criteria for each etiology found in our study are as follows.

TB meningoencephalitis was suspected when the clinical features of fever, night sweats, chronic cough, weight loss, altered sensorium, and past medical history of TB infection were present. Elevated lymphocytic-predominant pleocytosis, elevated protein and ADA levels, and low glucose levels in the CSF analysis were supportive of TB infection. In those cases, CSF was subjected to PCR to find TB, but TB treatment was still administered if the PCR test was negative but the other findings were highly suggestive of TB meningoencephalitis. Brain MRI, ESR, and the Mantoux test were also done to rule out contending diagnoses.

This entity was confirmed when MRI findings showed limbic system hyperintensities and the CSF analysis revealed a viral picture. Additionally, PCR testing of the CSF was done to find HSV. EEG results that showed diffuse slowing, focal temporal changes, periodic complexes, and periodic lateralizing epileptiform discharges were considered supportive features. If a patient responded to an empiric trial of acyclovir, the diagnosis of HSV encephalitis was made.

This diagnosis was made via the CSF analysis, blood cultures, and the elimination of competing diagnoses with imaging and laboratory tests. The CSF opening pressure and chemistry analysis can vary depending on the infectious agent. Still, in general, an increased pressure, neutrophilic pleocytosis, and low glucose level were considered supportive of a nonviral infection. When deemed appropriate, CSF gram stain, bacterial, and fungal cultures, India ink stain, cryptococcal antigen testing, and VDRL testing were conducted. Positive results were considered diagnostic.

AES patients with lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, or a normal ratio of CSF to plasma glucose in their CSF analyses had their serum tested for JE virus immunoglobulin M antibodies. A positive serum JE antibody test was considered diagnostic. Theta and delta coma, burst suppression, and epileptiform activity on EEG were deemed to be supportive features. MRI findings of bilateral hyperintensities in the thalamus and substantia nigra aided in the diagnosis.

Results supporting a potential inflammatory origin for the disease were confirmed with specific CSF tests for autoimmune antibodies against the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor, gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor A and B, contactin-associated protein-like 2 protein, or leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 protein. Positive neuronal surface or synaptic protein autoantibodies were considered diagnostic for this etiology.

TB meningoencephalitis was treated according to the National TB Management Guideline of Nepal [10]. Patients were given 2 months of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol followed by 7 to 10 months of isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol. Adjuvant dexamethasone was administered for up to 12 weeks. HSV encephalitis was treated with intravenous acyclovir at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 14 to 21 days. Bacterial meningoencephalitis was treated empirically using intravenous ceftriaxone and vancomycin. JE has no specific treatment; patients were hospitalized and provided with supportive care and close observation. All cases of autoimmune encephalitis were treated first with intravenous methylprednisolone. If the response was poor, patients were further treated with intravenous immunoglobulin or plasma exchange. Tumor surveillance was also done in all cases of autoimmune encephalitis.

We used IBM SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) to analyze the study data. Statistical analyses included the calculation of means, standard deviations, ranges, frequencies, and percentages. Independent sample t-testing was used to compare mean MoCA scores between male and female patients and between the 16–50 years age group and the 51–74 years age group. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with the Bonferroni post hoc analysis was used to compare mean MoCA scores among the different etiologies. A comparison of mean MoCA scores at different times was made using a paired t-test. To identify a variable to predict the MoCA score at the 3-month follow-up, we used a linear regression analysis. The prerequisite for the linear regression model was a linear relationship, normality, minimal multicollinearity, and no autocorrelation or homoscedasticity. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We enrolled 36 patients in our study (Figure 1). Fourteen patients (38.9%) were female, and 22 patients (61.1%) were male. Among the patients, 8.3% were aged 16 to 20 years, 61.1% were 21 to 50 years, and 30.6% were 51 to 74 years. The mean age of the participants in our study was 43 ± 18 years. Thirty-five patients (97.2%) were married. Thirty-one patients were Hindu (86.1%), two (5.6%) were Buddhist, two (5.6%) were Muslim, and one (2.8%) was Christian. Three patients (8.3%) were from province no. 1, 11 (30.6%) were from province no. 2, nine (25.0%) were from Baghmati province, three (8.3%) were from Gandaki province, six (16.7%) were from Lumbini province, one (2.8%) was from Karnali province, two (5.6%) were from Sudur Paschim province, and one (2.8%) was from Bihar, India.

The background laboratory characteristics of our patients are provided in Table 1. CSF total cell count, protein level, ADA, ESR level, and Mantoux diameter were all highest in TB meningoencephalitis patients. CSF neutrophil counts and CSF sugar levels were highest in bacterial meningoencephalitis patients. CSF lymphocyte counts were highest in TB meningoencephalitis and HSV encephalitis patients. The various comorbidities present in our study population are listed in Table 2.

Of our 36 patients with AES, TB meningoencephalitis was diagnosed in 14 cases (38.9%), HSV encephalitis in 14 (38.9%), bacterial meningoencephalitis in four (11.1%), autoimmune encephalitis in two (5.6%), and JE in two (5.6%) (Figure 1). Notably, the PCR results were positive in eight (57.1 %) of the 14 TB meningoencephalitis cases and 10 (71.4%) of the 14 HSV encephalitis cases. No specific organism could be cultured from two patients (50.0%) with bacterial meningoencephalitis, but the other two cases (50.0%) yielded Streptococcus pneumoniae. Both cases of autoimmune encephalitis were positive for NMDAR antibodies. The JE antibody test was positive in all cases of JE.

In our study, nine clinical features were charted for comparison among the etiologies; fever, headache, vomiting, convulsions, neck rigidity, Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s sign, photophobia, rash, and dystonia. The frequency of these features in each etiology is documented in Table 3. Fever and headache were seen in all 36 patients. Our study had only two cases of JE, and fever and headache were the only clinical features documented in those patients.

Of the remaining clinical features, neck rigidity was seen in 14 patients with TB encephalitis (100%), 12 patients with HSV encephalitis (85.7%), and four patients with bacterial encephalitis (100%). Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s sign was most commonly seen in TB meningoencephalitis (10, 71.4%), although it was also present in patients with bacterial (2, 50.0%) and HSV (4, 29.0%) encephalitis. Photophobia was reported in half of TB (7, 50.0%), bacterial (2, 50.0%), and HSV (7, 50.0%) encephalitis cases. Neck rigidity, Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s sign, and photophobia were not reported by patients with autoimmune encephalitis. Vomiting was experienced by eight patients with HSV encephalitis (57.1%), seven with TB encephalitis (50.0%), two with bacterial encephalitis (50.0%), and one with autoimmune encephalitis (50.0%). Convulsions were also seen in patients with encephalitis of HSV (2, 14.3%), TB (1, 7.1%), and autoimmune (1, 50.0%) etiologies, but they were most common in cases of bacterial meningoencephalitis (4, 100%). JE was the only cause that presented without vomiting or convulsions. Rash was present in one patient with bacterial meningoencephalitis (25.0%), and dystonia was seen in one patient with autoimmune encephalitis (50.0%).

The mean ± standard deviation values of the MoCA scores for various etiologies at different times are given in Table 4. MoCA at admission was highest in patients with bacterial meningoencephalitis. At discharge and follow-up, the MoCA scores were highest in HSV encephalitis and TB meningoencephalitis patients. We found statistically significant differences among the various etiologies in MoCA scores at admission, as determined by one-way ANOVA (F [4, 31] = 2.98, p = 0.034). To distinguish which etiological groups differed significantly from one another, a post hoc test was conducted. The Bonferroni post hoc test revealed that the MoCA score at admission was significantly lower in HSV encephalitis patients than in bacterial meningoencephalitis patients (mean difference, –6; standard error, 1.74; p = 0.017). One-way ANOVA showed no statistically significant differences among the etiologies in MoCA scores at discharge (F [4, 31] = 1.76, p = 0.16). Similarly, one-way ANOVA showed no differences among the etiologies in MoCA scores at the 3-month follow-up (F [4, 31] = 0.87, p = 0.493).

For each AES etiology, we used paired t-testing to evaluate increases in the mean MoCA scores between admission and discharge and between admission and the 3-month follow-up (Table 6). Among TB and HSV encephalitis patients, MoCA scores increased significantly at discharge and 3-month follow-up, compared with admission. In bacterial encephalitis, autoimmune encephalitis, and JE, the scores did not increase substantially from admission to discharge or 3-month follow-up.

A linear regression analysis was performed to find a predictor of the 3-month follow-up MoCA scores. We found that, holding all other variables constant, every unit increase in the MoCA score at discharge predicted a 0.96 unit increase in the MoCA score at the 3-month follow-up (p < 0.0001). The R2 value was 97.8%, indicating the excellent quality of this predictor (Table 7).

Disorders that affect the brain, activate the immune system and cause brain inflammation lead to the clinical presentation of AES. AES is a common neurological disorder with an estimated incidence of 1.5 to 7 cases/100,000 inhabitants/year, excluding epidemics [11]. Though encephalitis is a broad diagnosis with a vast range of known pathologies, roughly half of cases arise from an unknown etiology [11].

HSV encephalitis is the most common cause of AES worldwide and is responsible for 14% of the 20,258 AES patients admitted annually to hospitals in the United States [12]. We found that HSV encephalitis and TB encephalitis were equally common in Nepal, which contrasts with studies from other nations. Because Nepal is a low-income country, many Nepalis live with unsuitable housing, overcrowding, and inadequate sanitation, which foster the transmission of agents such as TB. Additionally, the problem of drug-resistant TB is magnified by inappropriate antibiotic use, non-adherence to TB regimens, and poor diagnostic facilities [13,14].

After TB and HSV, bacterial encephalitis was the third most common etiology in our study. We also had two cases of autoimmune encephalitis and two cases of JE in our study population. JE is a significant public health problem in Asia, accounting for 50,000 cases and 15,000 deaths annually in the region [3]. Although Nepal lies in an area with endemic JE, its prevalence was low in our study. It is principally considered a disease of children; therefore, our rate might have been low because we excluded patients younger than 16 years [3]. Furthermore, JE outbreaks occur most commonly in the monsoon season, especially in the Terai belt of Nepal, and most cases are managed in local districts or provincial hospitals [15]. The Kathmandu Valley lies in the hill belt of Nepal, with minimal mosquito transmission and thus low disease activity. Only complicated cases from the Terai belt are referred to Kathmandu Valley, and our low proportion of JE cases likely reflects those facts.

Our study population contained 14 female and 22 male patients, which is in accordance with the proportions reported in other studies [7-10] and suggests that AES is more common in males. Increased outdoor activity, contact exposure, and stress are potential explanations for this discrepancy. Another reason might be social stigma or low health-seeking behavior among women, leading to a falsely reduced presentation rate in this population. The current literature has reported age, sex, and level of education to be the factors most predictive of a patient’s MoCA score [16,17]. Higher levels of education and female sex have been associated with higher scores, and older age is associated with lower scores [16]. Although the cognitive profiles of male and female patients in our study did not differ significantly from each other, we found that MoCA scores at discharge and the 3-month follow-up were significantly higher in patients aged 16 to 50 years than in those aged 51 to 74 years. Several variables could be responsible for that finding. MoCA examinations were not conducted before AES onset, so we cannot establish how well the follow-up scores reflect each age group's baseline function. Cognitive impairment is more common among older people and could therefore be a contributing factor to the lower scores in the group of 51- to 74-year-old patients. Additionally, the MoCA assessment has been validated for the detection of cognitive impairment only in individuals aged 55 to 85 years, which could have resulted in less accurate analysis of our younger patients’ cognition [9]. Although no difference was seen between male and female patients in our study, normative data from a large population-based cohort found the effect sizes of age and education on MoCA scores to be twice that of sex [9]. Because women are less likely than men to receive formal education in Nepal, the educational difference might have contributed to the lack of significance we found between the sexes.

We observed that among TB and HSV patients, the MoCA score increased significantly at discharge and the 3-month follow-up compared with admission. Specific treatments available for TB meningoencephalitis and HSV encephalitis could be related to that improvement [1,18]. Among bacterial encephalitis patients, the MoCA score at admission did not increase significantly at discharge or 3-month follow-up. Bacterial meningoencephalitis is associated with a fulminant course, contributing to poor cognitive function among its patients. Additionally, the growth of bacteria from CSF cultures is often difficult, making empiric treatment, which might not always be effective, common in these cases [19]. In patients with autoimmune encephalitis, MoCA scores at admission did not increase significantly at discharge or 3-month follow-up.

In low-income countries where infectious etiologies are common, work-up and treatment for autoimmune encephalopathies occur later in the clinical timeline. Significant diagnostic delay is therefore expected in cases of autoimmune encephalitis. Autoimmune encephalitis is treated with nonspecific modalities, including corticosteroid regimens, that are not always adequate to prevent relapse and neurological sequelae. Intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, and second-line drugs such as rituximab are not readily available or affordable in low-income countries [20]. JE patients face a similar situation of nonspecific treatment guided mainly by symptom management. A minimal, nonsignificant increase in MoCA scores at discharge and 3-month follow-up was seen in these two populations [5,7].

The research on cognitive impairment in encephalitis is scant. Hébert et al. [21] observed that 52% of 21 individuals with autoimmune encephalitis showed persistent cognitive impairment at their last follow-up (median of 20 months). Visuospatial and executive abilities, language, attention, and delayed recall were predominantly affected. They also discovered that shorter treatment delays and no status epilepticus at onset were linked to greater MoCA scores more than a year later, possibly predicting better long-term cognitive results. A study by Hang et al. [22] reported that 90.48% of 21 autoimmune encephalitis patients experienced short-term memory loss. After therapy, it dropped to 14.29%. A MoCA-B score 6.19 points higher than the onset score was observed at the 1-year follow-up (p < 0.001).

Three studies have considered the cognitive outcomes of TB meningitis patients. Ganaraja et al. [23] found that TB meningitis patients had impaired results in auditory verbal learning (88.3%), complex figure (50%), spatial span (50%), clock drawing (48.3%), digit span (35%), color trail 1 and 2 (30% and 33.3%, respectively), and animal naming (28.3%) tests. Treatment improved the animal naming, clock drawing, color trail 2, spatial span, and digit span test results. Verbal learning showed no change. Overall, neuropsychological testing revealed improved attention, working memory, and category fluency but minimal language learning recovery [23]. In two other cohort studies from India (n = 30 and 65, respectively), patients were evaluated using the 30-point Mini-Mental State Exam 6 months [24] and 1 year [25] after their TB meningitis diagnoses. Using cutoff scores of 22 to 29, depending on education level, more than half of the patients tested (54% and 55%, respectively) sustained cognitive impairments.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small. Second, individual cognitive domains in the MoCA tool were not evaluated or analyzed. Third, some patients were illiterate, which rendered cognitive testing with the MoCA difficult. The MoCA test was modified to suit our study’s Nepalese context, which could have resulted in bias. Fourth, we acknowledge that 3 months is too short a period to fully evaluate cognitive outcomes after AES. Fifth, our sample contained only a few JE patients, even though JE is one of the commonest causes of AES in this part of the world.

In conclusion, we found that AES patients with low cognitive function can improve with active treatment. At discharge and follow-up, AES patients with treatable causes such as TB meningoencephalitis and HSV encephalitis saw statistically significant improvements in their cognitive functioning. Although infectious etiologies are most common in low-income countries such as Nepal, autoimmune etiologies should not be overlooked. Early testing for autoantibodies could reduce cognitive sequelae by offering timely diagnosis and treatment. Continued research is warranted to improve the early diagnosis of AES and understanding of the cognitive sequelae that can follow.

Table 1

Baseline laboratory parameters for various etiologies of acute encephalitis syndrome

Table 2

Comorbidities present in the patients in this study

Table 3

Clinical features of various causes of acute encephalitis syndrome

Table 4

The MoCA scores at different times

Table 5

Comparison of MoCA score among various age groups and sexes using independent sample t-testing

Table 6

Paired t-test to evaluate increases in the mean scores on the cognitive assessment test between admission and discharge (A) and admission and 3-month follow-up (B)

Table 7

Linear regression analysis showing predictors of MoCA score at the 3-month follow-up

References

1. Venkatesan A, Geocadin RG. Diagnosis and management of acute encephalitis: a practical approach. Neurol Clin Pract 2014;4:206–215.

2. Ghosh S, Basu A. Acute encephalitis syndrome in India: the changing scenario. Ann Neurosci 2016;23:131–133.

3. Solomon T, Dung NM, Kneen R, Gainsborough M, Vaughn DW, Khanh VT. Japanese encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:405–415.

4. Joshi R, Mishra PK, Joshi D, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and survival in adult acute encephalitis syndrome in rural Central India. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013;115:1753–1761.

5. Verma A, Tripathi P, Rai N, et al. Long-term outcomes and socioeconomic impact of Japanese encephalitis and acute encephalitis syndrome in Uttar Pradesh, India. Int J Infect 2017;4:e15607.

6. Thakur KT, Motta M, Asemota AO, et al. Predictors of outcome in acute encephalitis. Neurology 2013;81:793–800.

7. Kakoti G, Dutta P, Ram Das B, Borah J, Mahanta J. Clinical profile and outcome of Japanese encephalitis in children admitted with acute encephalitis syndrome. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:152656.

8. Davis AG, Nightingale S, Springer PE, et al. Neurocognitive and functional impairment in adult and paediatric tuberculous meningitis. Wellcome Open Res 2019;4:178.

9. Nasreddine Z. MoCA Test: MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment [Internet]. Greenfield Park (QC): MoCA Test Inc; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.mocatest.org.

10. National Tuberculosis Centre. National tuberculosis management guidelines, 2019 [Internet]. Thimi, Bhaktapur: National Tuberculosis Centre; 2019 [cited 2021 Jun 15]. Available from: http://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National-Tuberculosis-Management-Guidelines-2019_Nepal.pdf.

11. Boucher A, Herrmann JL, Morand P, et al. Epidemiology of infectious encephalitis causes in 2016. Med Mal Infect 2017;47:221–235.

12. Vora NM, Holman RC, Mehal JM, Steiner CA, Blanton J, Sejvar J. Burden of encephalitis-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1998-2010. Neurology 2014;82:443–451.

13. Marahatta SB, Yadav RK, Giri D, et al. Barriers in the access, diagnosis and treatment completion for tuberculosis patients in central and western Nepal: a qualitative study among patients, community members and health care workers. PLoS One 2020;15:e0227293.

14. Marahatta SB, Kaewkungwal J, Ramasoota P, Singhasivanon P. Risk factors of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in central Nepal: a pilot study. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2010;8:392–397.

16. Borland E, Nägga K, Nilsson PM, Minthon L, Nilsson ED, Palmqvist S. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: normative data from a large Swedish population-based cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;59:893–901.

17. Larouche E, Tremblay MP, Potvin O, et al. Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in middle-aged and elderly Quebec-French people. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2016;31:819–826.

18. Davis A, Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ. Treatment of Tuberculous meningitis and its complications in adults. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2018;20:5.

19. Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1267–1284.

20. Lancaster E. The diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune encephalitis. J Clin Neurol 2016;12:1–13.

21. Hébert J, Day GS, Steriade C, Wennberg RA, Tang-Wai DF. Long-term cognitive outcomes in patients with autoimmune encephalitis. Can J Neurol Sci 2018;45:540–544.

22. Hang HL, Zhang JH, Chen DW, Lu J, Shi JP. Clinical characteristics of cognitive impairment and 1-year outcome in patients with anti-LGI1 antibody encephalitis. Front Neurol 2020;11:852.

23. Ganaraja VH, Jamuna R, Nagarathna C, Saini J, Netravathi M. Long-term cognitive outcomes in tuberculous meningitis. Neurol Clin Pract 2021;11:e222–e231.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0

- 5,455 View

- 58 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Parash Rayamajhi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2223-4276 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print