Behavioral tasks

Following the sequential experiences of MS, SD, and SI, the MS/SD/SI mice performed behavioral tasks to assess anxiety, locomotor activity, learning/memory, social behavior, aggression, fear, and despair. The behavioral tests were video-recorded and conducted between 13:00 and 18:00 under a light intensity of 80 lux. There were no experimenters in the room during the behavioral tasks, which comprised elevated plus maze, light/dark transition, marble-burying, nest-building, open-field, classical fear-conditioning, observational fear-conditioning, predator fear, resident-intruder, social interaction with a juvenile mouse, sociability, and forced swim (FST) and tail-suspension tests (TSTs). Data were quantified by an experimenter blinded to the conditions. Behavioral experiments were performed as described previously [

23-

29].

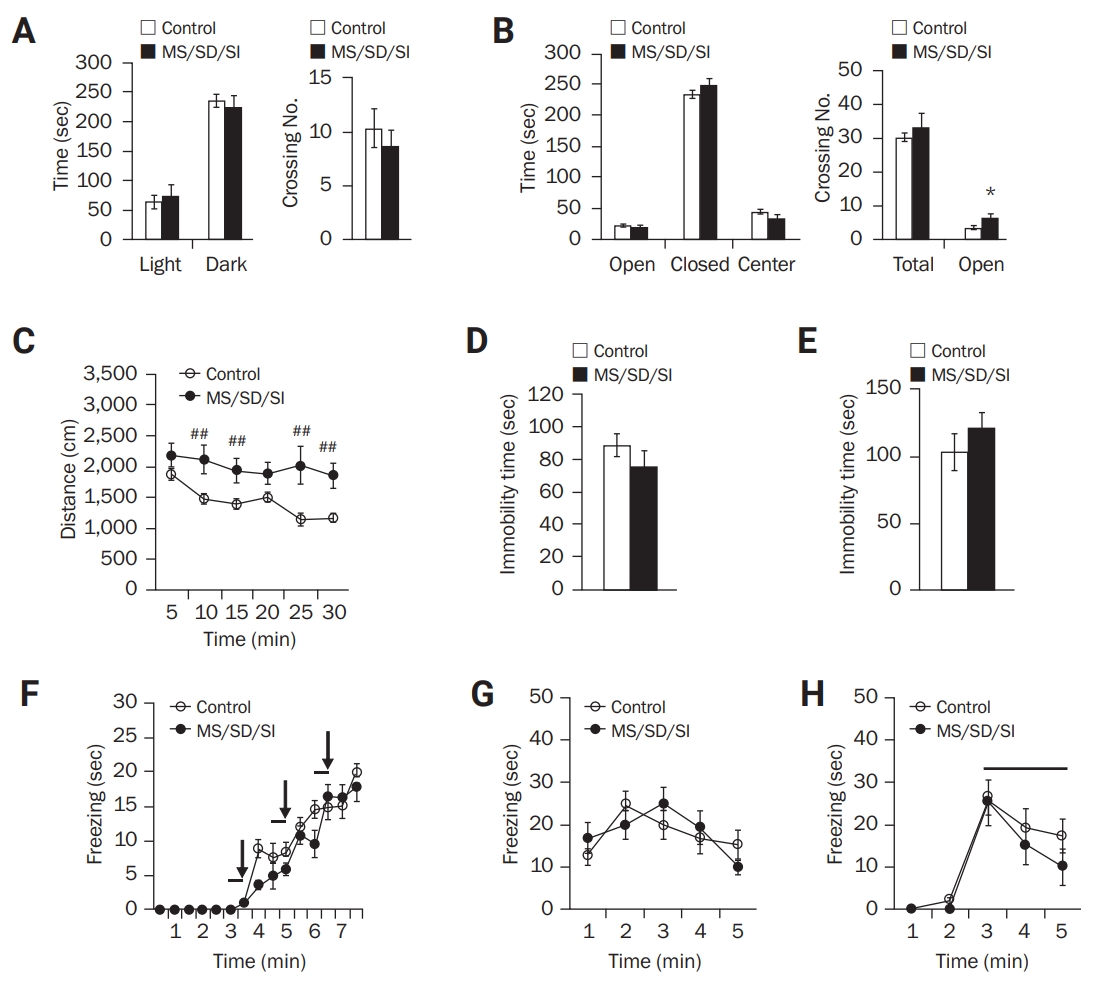

The elevated plus maze was made of plastic and consisted of two white open arms (25 × 8 cm), two black enclosed arms (25 × 8 × 20 cm), and a cross-shaped central platform (8 × 8 × 8 cm). The maze was placed 50 cm above the floor, and mice were individually placed in the center with their heads directed toward one closed arm. The total time spent in each arm or in the center and the total number of entries into each arm were analyzed by video monitoring for 5 minutes. When all four paws crossed from the center into an arm, it was counted as an arm entry.

The light/dark transition test was performed using a plastic light/dark box (30 × 45 × 27 cm) composed of a dark compartment (1/3 of the total area) and a light compartment (2/3 of the total area), with a hole between the two. The light compartment was illuminated at 400 lux. The elapsed time to entry into the light compartment (latency) and the amount of time (duration) spent in each compartment were measured over a 5-minute period by video monitoring.

In contrast, the open-field box was made of white plastic (40 × 40 × 40 cm). Individual mice were placed in the periphery of the field, and the paths of the animals were recorded with a video camera. The total distance traveled for 30 minutes was analyzed using EthoVision XT (Noldus, Wageningen, Netherlands).

For the FST, mice were placed individually in 2,000-mL glass beakers filled with nearly 1,400 mL of water (10 cm from the ground, with a water temperature of 25°C ± 1°C) and were allowed to swim freely for 6 minutes. The duration of immobility, defined as lack of movement in a floating state or performance of only minimal movement required for floating (e.g., small, slow kicking of one paw only) but the absence of active swimming behavior, was measured during the last 4 minutes of the task.

During the TST, mice were hung upside down from a horizontal bar by the tail. Mouse behavior was recorded for 6 minutes, and the time spent immobile was measured.

For classical fear-conditioning, the mice were habituated in a fear-conditioning apparatus chamber for 5 minutes and then subjected to a 28-second acoustic conditioned stimulus followed by a 0.7-mA shock (unconditioned stimulus) applied to the floor grid for 2 seconds (Panlab SLU, Barcelona, Spain). Conditioned stimulus–unconditioned stimulus coupling was carried out three times at 60-second intervals. To assess contextual memory, the animals were placed back into the training context 24 hours after the stressful experiences. The duration of their fear response (freezing behavior) was measured for 4 minutes. To assess the cued memory, the animals were placed in a different context (a novel chamber) for the following 24 hours, and their behavior was monitored for 5 minutes. During the last 3 minutes of this test, the animals were exposed to the conditioned stimulus. Their duration of freezing behavior was measured throughout the 3-minute test.

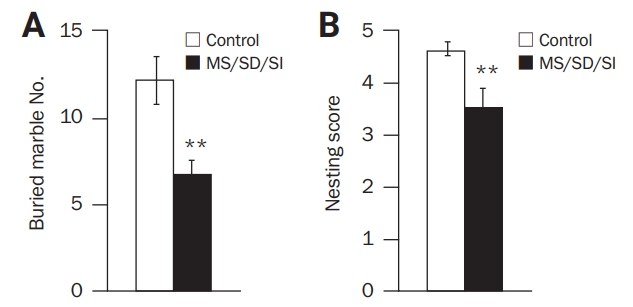

During the marble-burying test, a single subject mouse was allowed to roam freely in a clean cage (22 × 19 × 17 cm, with a 5-cm sawdust layer) for 10 minutes for habituation. Then, the mouse was removed while 20 glass marbles (15 mm in diameter) were randomly placed in the cage; the subject mouse was reintroduced and allowed to roam freely for 20 minutes. The number of marbles buried (defined by > 50% of the marble being covered by bedding material) was recorded.

For the nest-building test, each mouse was briefly moved to a cage with wood-chip bedding and one Nestlet (Ancare, Bellmore, NY, USA) approximately 1 hour before the dark phase. The following morning, we assessed the nest-building status on a rating scale of 1 to 5 points, as follows: 1, the Nestlet was largely untouched (> 90% intact); 2, the Nestlet was partially torn up (50%–90% remaining intact); 3, the Nestlet was mostly shredded (< 50% remaining intact), but there was no identifiable nest site; 4, there was an identifiable but flat nest (walls higher than mouse height but < 50% of the nest circumference); and 5, there was a well-formed nest with a crater (walls higher than mouse height and ≥ 50% of the nest circumference).

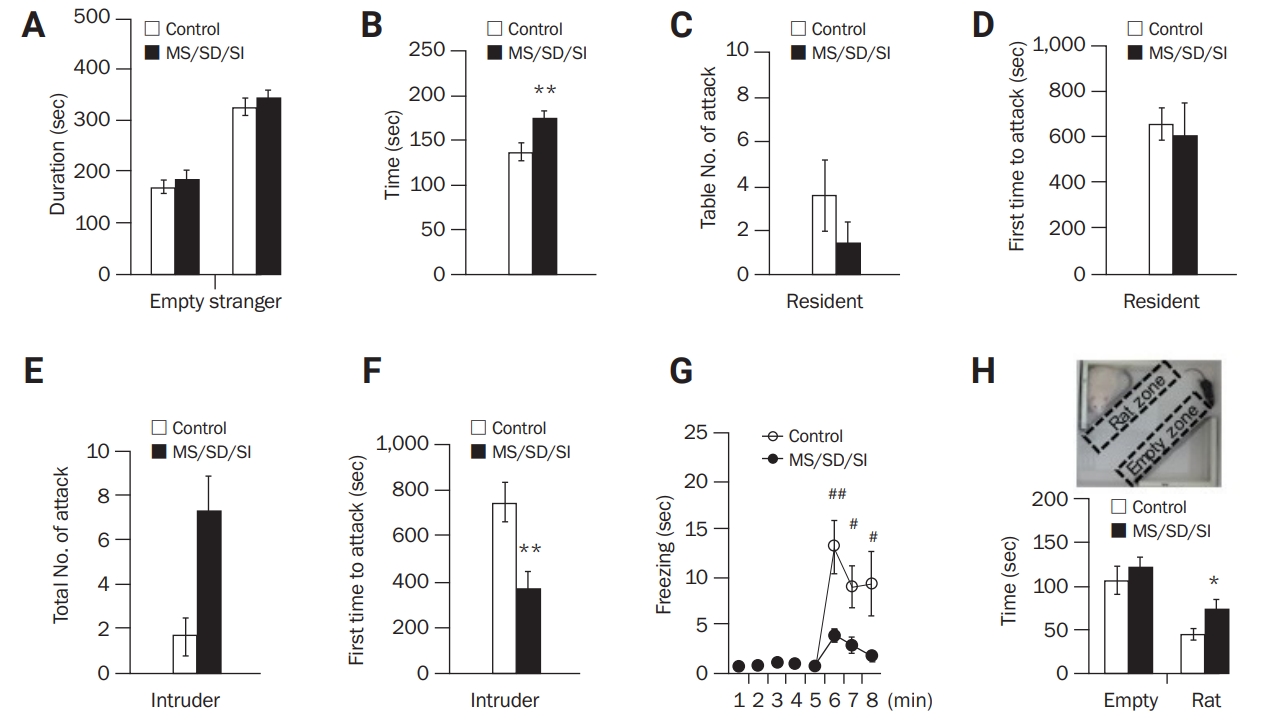

During the sociability task, a three-chambered, white, rectangular plastic box (40 × 25 × 18 cm) was used, into which a wire mesh cage (diameter, 8 cm; height, 10 cm) was placed in each of two side chambers (facing diagonally in the box). Following a 10-minute habituation period, a novel mouse (stranger, age-matched male C57BL/6 mouse) was enclosed in one of the wire cages, and the subject mouse was placed in the middle of the box and allowed to explore for 10 minutes. The time spent in each chamber was measured.

For the social interaction task, a single subject mouse in its home cage was allowed to roam freely for 10 minutes (habituation). A novel juvenile (3–4 weeks old) male C57BL/6 mouse was introduced into the home cage of the resident subject, and both were allowed to roam freely for 5 minutes (test session). The following types of behavior shown by the resident mouse were scored as social interaction: sniffing, grooming, closed chasing, pushing the snout or head under, and crawling over or under the juvenile’s body, as well as mounting. The total time spent performing social interaction behaviors was quantified.

The isolation-induced resident-intruder aggression test was performed by introducing an intruder mouse into the home cage of the resident mouse. Resident mice were housed in isolation for 7 days without a bedding change before testing. Aged-matched, naïve male C57BL/6 mice were used as counterparts. The offensive behavior of the resident (offensive aggressiveness) or intruder mouse (defensive aggressiveness) was measured by the latency to the first attack and the total number of attacks (biting and wrestling) by either for 15 minutes.

For observational fear-conditioning, the apparatus consisted of a dual-channel modular shuttle box consisting of two identical chambers (21 × 17.5 × 25 cm each) and a stainless-steel rod floor (5-mm–diameter rods, spaced 1 cm apart; Med Associates, Albans, VT, USA). A transparent plexiglass partition was placed between the chambers. Briefly, the observer and demonstrator mice (age-matched male C57BL/6 mouse) were habituated in the apparatus chambers for 5 minutes. Then, a 2-second foot shock (1.3 mA) was administered to the demonstrator every 10 seconds for 3 minutes by a computer-controlled shocker (Med Associates). The duration for which the observer mouse displayed freezing behavior (fear response) was measured.

Finally, the predator-avoidance test was designed by modifying the social approach-avoidance test or social target test. The test area was a white acryl plastic open-field box (40 × 40 cm) that contained two triangular wire mesh cages (21 × 21 × 28 cm) located diagonally across each end of the field. One cage (target) contained a social target animal (male rat, 5–10 weeks), and the other cage (no target) was empty. Video-tracking data were used to determine the times spent by the experimental mouse in the “rat zone” and “empty zone” (28 × 6 cm) in front of each cage.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print