Introduction

Eosinophilia in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a rare finding, reported in less than 3% of total lumbar puncture samples [

1]. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis is diagnosed based on clinical manifestations and laboratory findings of CSF eosinophil counts higher than 10 per mL or 10% of the total CSF leukocyte count [

2,

3]. In most cases, helminthic infections of the central nervous system are identified as the cause, most commonly

Angiostrongylus cantonensis and

Taenia solium in endemic areas. Infectious agents other than parasites and non-infectious causes have also been reported [

3].

The clinical course of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis varies depending on the causative agent and the severity of inflammation, and medical intervention is required in many cases. In addition to treatment of the inciting agent, sufficient control of inflammation is key to minimizing neurological sequelae. Corticosteroids are widely used as the first-line anti-inflammatory treatment, and most patients show good response to adequate doses [

3]. However, there have been cases where patients continued to deteriorate despite adequate corticosteroid therapy, leading to permanent neurological damage or death [

4]. To date, the use of alternative anti-inflammatory agents in eosinophilic meningoencephalitis has not been reported. We report a case of idiopathic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis with insufficient response to corticosteroid therapy treated successfully with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Case Report

A previously healthy 68-year-old male presented to the emergency department with persistent fever and progressively worsening consciousness. One month prior, he had been bitten by an unknown insect and, from that day on, suffered flu-like symptoms with generalized malaise, myalgia, fever, and headache. Ten days later, he showed symptoms of disorientation, memory impairment, incontinence, and progressive gait disturbance that necessitated admission to a local hospital. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the local hospital was unremarkable. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed pneumonic infiltrates consistent with atypical pneumonia, which prompted antibiotic treatment. Despite 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment, fever persisted with aggravation of mental status, and the patient was referred to our hospital for further evaluation.

Initial vital signs were in the normal range. On examination, the patient was afebrile and had no evidence of rash on the skin or any lymphadenopathy. Chest and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. Neurological examinations showed drowsy mental status with Glasgow Coma Scale scores of eye opening of 3, verbal response of 3, and motor response of 5 (E3V3M5). He was disoriented, responded only to his name, and could not follow simple commands. Motor examination showed general weakness, and deep tendon reflexes were normoreflexive. Nuchal rigidity was present, with positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs.

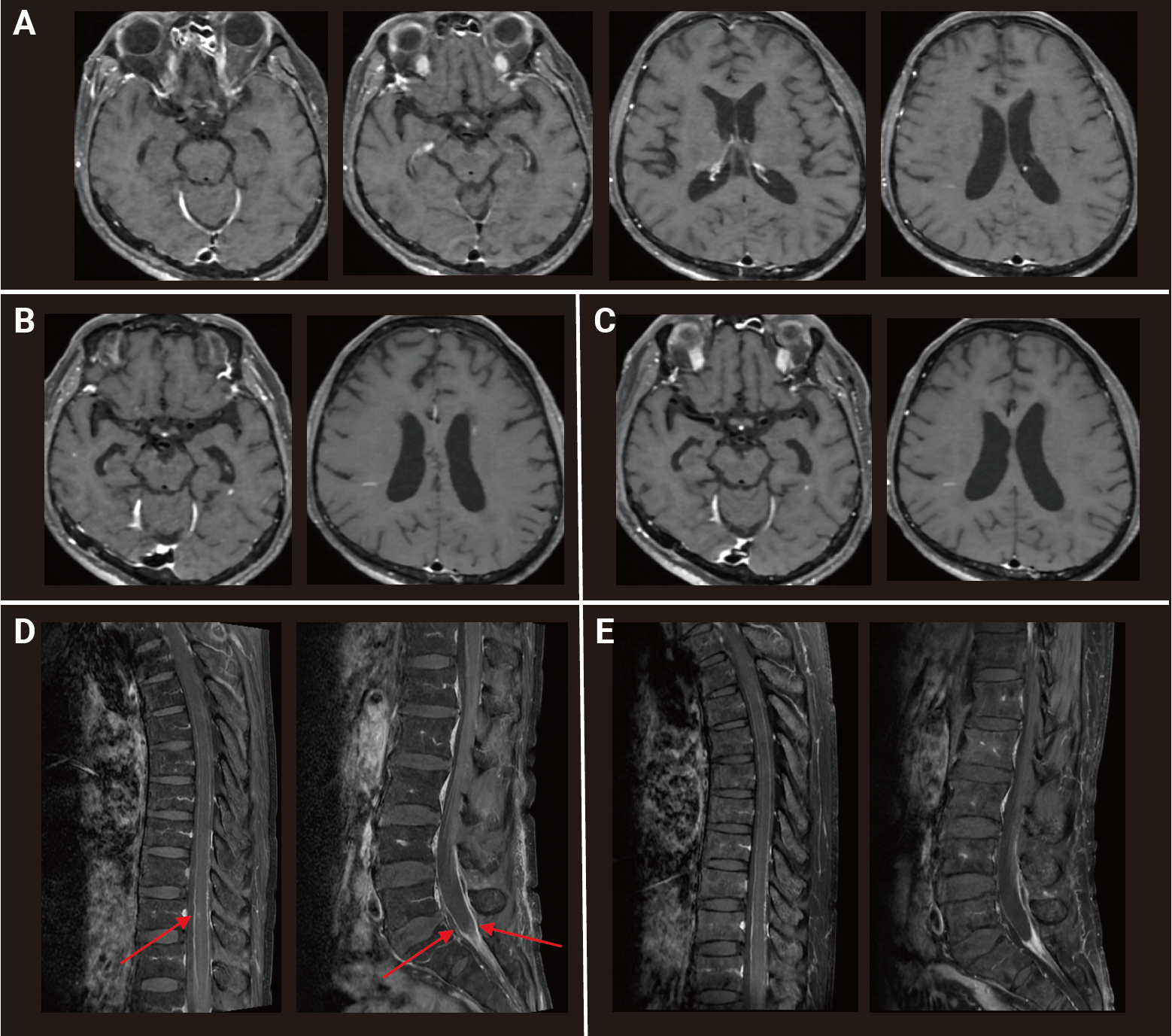

Peripheral eosinophilia (6.2%; absolute count, 471 cells/μL) was identified in complete blood count without leukocytosis. Mild elevation of alanine transaminase at 70 IU/L (normal range, 1–40 IU/L) and C-reactive protein at 1.43 mg/dL (normal range, 0–0.5 mg/dL) was present, but routine laboratory test results were otherwise unremarkable. CSF findings revealed lymphocyte-dominant pleocytosis 320 leukocytes/μL, 42% lymphocytes, protein elevation at 246 mg/dL, and low glucose at 23 mg/dL. Additional chest CT scans showed interval-increased (compared to 2 weeks prior), ill-defined nodules with ground glass opacities suggestive of simple eosinophilic pneumonia. Gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI revealed multiple small enhanced lesions without diffusion restriction and minimal perilesional edema in the left lateral and medial temporal lobe, corpus callosum, right lateral ventricle wall, and cerebellum, suggestive of meningoencephalitis (

Figure 1A). A spinal cord MRI was performed due to incontinence and revealed leptomeningeal enhancement along the spinal cord and cauda equina nerve root surface and a focal intramedullary T2 high-signal-intensity lesion with enhancement at T10 and T11 (

Figures 1B and

C). Initial electroencephalography (EEG) findings showed rhythmic delta activities.

The diagnosis was meningoencephalitis, and the patient was started on empirical ampicillin, ceftriaxone, vancomycin, doxycycline, and acyclovir along with concomitant coverage of intravenous (IV) dexamethasone (10 mg, every 6 hours for 4 days) since infectious causes could not be ruled out initially. Lacosamide treatment was initiated due to EEG findings. Within a few days of treatment, the patient showed remarkable improvement and could attend to daily activities with minimal assistance. Yet, memory impairment with a Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) score of 22 out of 30 and neurogenic bladder persisted, along with mild fever.

Additional etiologic work-up was performed to elucidate the cause of inflammation. Cytospin results of the initial CSF showed eosinophilia of 29%, serum immunoglobulin E was elevated to 740 IU/mL (normal range, 0–100 IU/mL), and serum parasite-specific antibody immunoglobulin G (IgG) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was positive for cysticercosis (0.465; positive cutoff value, 0.29) and borderline positive for sparganosis (0.261; positive cutoff value, 0.24). The CSF IgG index was elevated to 1.65 (normal range, <0.66), and CSF oligoclonal bands were positive with a type 2 pattern showing more than two bands. Cytologic examinations of the CSF were negative for any malignant cells or possible pathogens, and 16S rDNA analysis of the CSF showed no evidence of bacterial pathogens. Tests for other infectious and inflammatory causes were all negative (

Table 1). Follow-up lumbar puncture after 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment showed slight but not significant improvement in CSF profile (255 leukocytes/μL, 24% eosinophils, protein 104 mg/dL) (

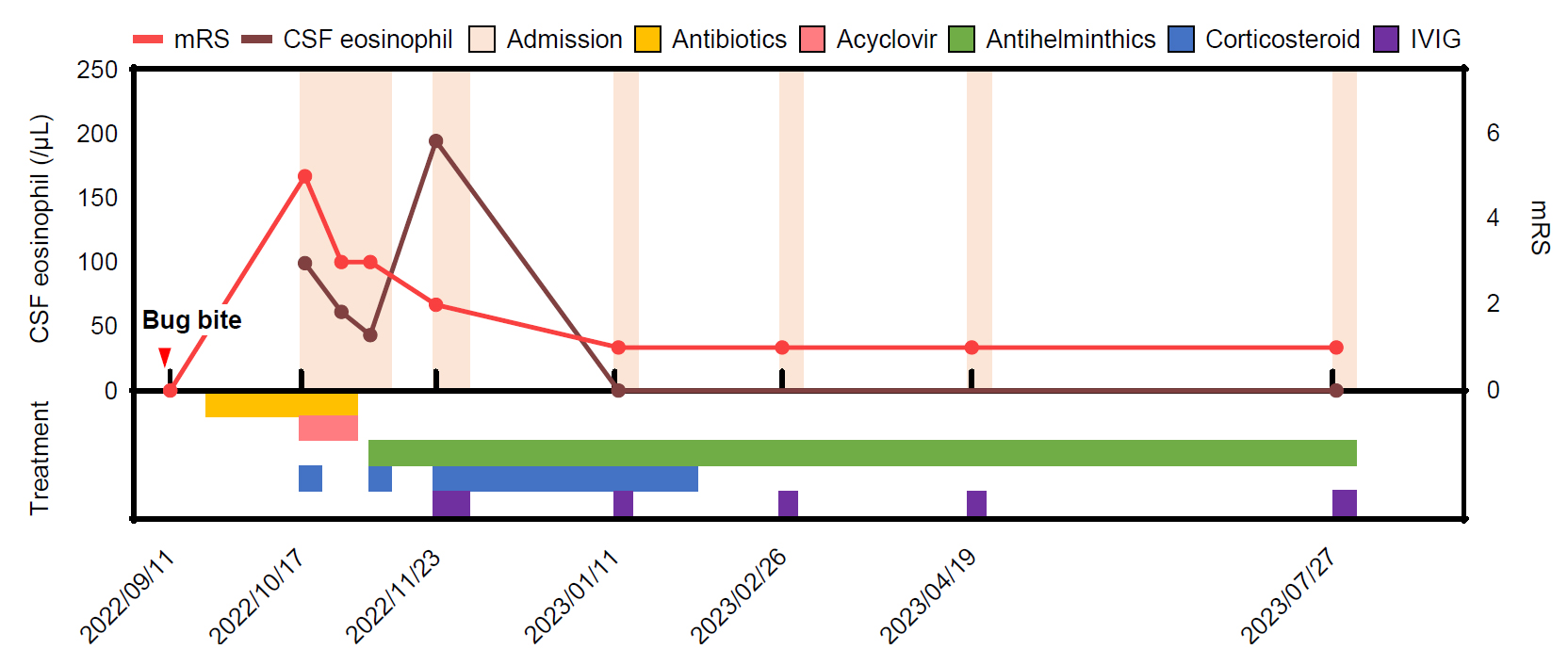

Figure 2).

The final diagnosis was eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, and idiopathic systemic hypereosinophilia or neurocysticercosis was considered as the causative agent. The patient was treated with IV methylprednisolone (500 mg daily for 5 days) for inflammatory control and concomitant treatment with albendazole and praziquantel for the possibility of neurocysticercosis. The patient was discharged on a combination of albendazole and praziquantel treatment and was readmitted 3 weeks later for follow-up. Despite an improved K-MMSE score of 28 out of 30, the CSF profile showed aggravation of inflammation (626 leukocytes/μL, 31% eosinophils, protein 110 mg/dL) and persistence of inflammatory lesions on brain MRI. Along with oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg), IV immunoglobulin (IVIG; 2 g/kg over 5 days) was added to the treatment plan due to suboptimal treatment response with corticosteroid use to target ongoing inflammation. Two months later, a follow-up brain MRI showed a significant decrease in the extent of initial multiple enhanced lesions, and the CSF profile had normalized (2 leukocytes/μL, 0% eosinophils, protein 33 mg/dL). K-MMSE score was 29 out of 30, and the patient reported a normal state. Oral prednisolone was tapered off, and the patient was maintained on regular maintenance doses of IVIG every 2 months for an additional 6 months. At the end of treatment, brain and spinal cord imaging showed no additional lesions, and his CSF profile remained normal without signs of inflammation (4 leukocytes/μL, 0% eosinophils, protein 39 mg/dL). The patient is currently on regular follow-up via the outpatient clinic without neurologic signs or symptoms.

Discussion

Eosinophilia in the CSF is a rare clinical finding, and while most cases in the literature report helminthic infection as the cause, the etiology remained idiopathic in our patient even after extensive work-up. In helminthic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, the consensus in treatment is to use anthelmintic drugs according to the identified parasite, along with corticosteroid treatment [

3,

5]. However, treatment decisions can be challenging in idiopathic cases and no guidelines exist. To obtain an overview of how such cases are managed in the real world, we performed a literature review using the MEDLINE database. The main search terms were “eosinophilic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, encephalitis,” with a search period from January 1, 1957 to January 31, 2024. Additional references were added based on the review of selected papers. Papers without abstracts available in English were excluded. All papers were reviewed manually to exclude those that did not meet the criteria of eosinophils >10% of the total CSF leukocyte count and cases in which the causative agent was identified by confirmative diagnostic testing. The initial search retrieved 181 articles. Of them, 108 were excluded either because no abstract was available, the study was conducted in animals, or the article was unrelated to the topic. In the remaining 73 papers, 14 were cohort studies or review articles, and 58 were case reports or case series. After excluding helminthic cases, 14 cases of idiopathic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis were finally identified (

Table 2) [

6-

19].

In the included studies, eosinophilia in CSF ranged from 10% to 84%. Five of the cases were suspected to be drug-related, three cases occurred after myelography with iophendylate contrast media, three cases were presumed to be associated with other forms of malignancy, and three cases were thought to be related to other inflammatory conditions. Regarding treatment, all but five cases presumed to be drug- or contrast-related used corticosteroid treatment in either oral or IV form. Depending on the associated conditions, adjunctive treatments such as antibiotics, anticancer treatment, or antihistamines were co-administered. In the nine cases that used corticosteroid treatment, full recovery was observed in four cases, partial response in four cases, and death occurred in three cases. Two of the deaths occurred in patients who seemed to have shown partial neurological improvement after corticosteroid administration.

Based on the literature review, corticosteroids seem to be the mainstay of treatment in cases of idiopathic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, regardless of the associated condition. While at least a partial response was observed in most cases, some patients showed insufficient improvement with corticosteroids alone as the anti-inflammatory treatment. Our patient also showed persistence of neurologic symptoms and evidence of neuroinflammation after treatment with corticosteroids. Although in our case, the exact etiology is unknown, inflammation persisted 2 months after the initial inciting insect bite, even after two full cycles of steroid pulse therapy. The addition of IVIG greatly aided in inflammatory control and, at regular maintenance doses, proved to be sufficient in long-term inflammation control.

The mechanism by which IVIG proved effective in our patient is unknown. The absence of pathogens in idiopathic cases of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis implies that eosinophilia in the CSF itself can cause neuronal damage leading to symptoms. Gordon [

20] and Durack et al. [

21,

22] showed that eosinophil-derived-neurotoxin can serve as a neurotoxic agent. Meanwhile, IVIG treatment has been reported in other types of eosinophilic diseases, such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome especially in refractory cases, although the exact mechanism of action is unknown [

23-

25]. Hence, IVIG may provide direct modulatory effects on the activation of eosinophils or on secondary damage caused by eosinophil-derived neurotoxic agents.

The presence of CSF oligoclonal bands was reported in a few cases [

6], as well as in our case, which suggests the presence of intrathecal IgG synthesis. In a study on intrathecal synthesis of immunoglobulins in eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis was observed in all cases 7 days after symptom onset [

26]. In that study,

A. cantonensis infection was the etiology, and the intrathecal synthesis was interpreted as a neuroimmunological response to the parasite and its toxins. However, no specific pathogen was identified in our patient; thus, the synthesis of intrathecal immunoglobulins may have been a secondary immunological response to damage-associated molecular pattern signals generated by the primary neurotoxic activity of eosinophils. IVIG might have shown an effect by modulating this secondary immunological response.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report on successful treatment of idiopathic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis using IVIG. Although the exact mechanism of action warrants further study, this report suggests the possibility of IVIG as a secondary agent for the control of neuroinflammation in eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, especially when corticosteroid use is undesirable or results in insufficient clinical improvement.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print